Attachment theory and relationships

Attachment theory and relationships

I’m surprised that I’ve never tackled this one in a blog because I talk about it ALL THE TIME in session! And I should flag that there’s a lot of great online resources that I’ll share at the end of this week’s blog because I’m totally down with having as much information and insight as possible on our patterns of behaviour that can stem from our attachment style.

‘Attachment’ as I concept emerged with research conducted by John Bowlby (who himself had an interesting experience of childhood attachment that influenced his work) and later Mary Ainsworth in the 1960s. Their work was around the bond between a (primary) caregiver and their infant. The premise of this work can be conceptualised as the confidence that we have in our parent (caregiver / attachment figure) to provide us with a ‘secure base’ (from which we can freely explore the world around us) and a ‘safe haven’ (a place we know where we can turn to for comfort). However, attachment doesn’t end in childhood and is active throughout our lives influencing how we navigate friendships and also romantic relationships. In this way, our primary attachment forms a template for our future relationships, however, trauma and healing can lead to changes in this so remember that our attachment styles do not remain fixed throughout our lives.

Attachment styles:

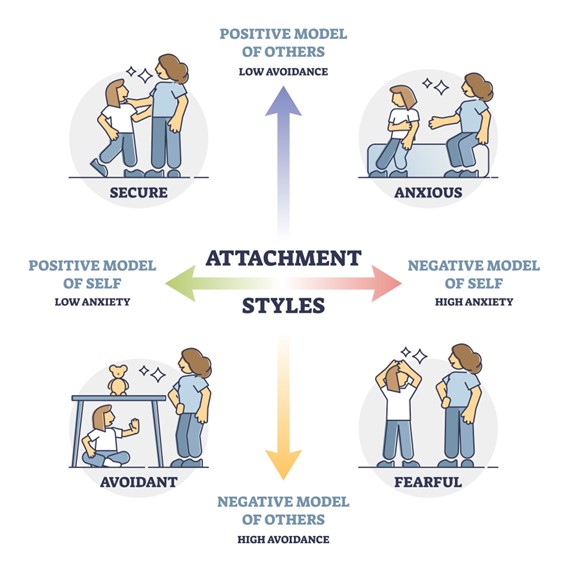

- Secure – as adults are comfortable with intimacy and can balance both dependence and independence within relationships. In childhood this probably came from a place of feeling safe, understood and valued and being able to ask for reassurance or validation without punishment. Parents/caregivers were likely to be emotionally available and aware of their own emotions and behaviour (and their impact).

- Preoccupied (anxious) – crave intimacy and can be overly dependent and demanding in adult relationships. Is characterised by fears of rejection and/or abandonment. In childhood this probably stemmed from inconsistent parenting or where parents/caregivers weren’t attuned to the needs of their child.

- Dismissive (avoidant) – strong sense of self-sufficiency, often to the point of appearing detached. This can look like a failure to build long-term relationships related to the inability to engage in meaningful physical and emotional intimacy. In childhood, caregivers might have expected high levels of independence or rejected the expression of needs / emotions.

- Fearful (disorganised) – desire close intimate relationships but fear the vulnerability required to develop this and this can result in apparently conflicted and unpredictable behaviours in relationship. In childhood this often stems from childhood trauma, neglect or abuse – but can also come from fear of caregivers (noting that this can be perception of fear).

Perhaps something to understand is that attachment styles are related to both an internal (self) cognition, related to ‘am I worthy of love’ and external (other) cognition, related to ‘can I depend on others in times of stress’. In this way, by adulthood we have developed either a positive or negative belief of both self and other in relationship. Securely attached adults tend to hold positive images of both self and others, meaning that they have both a strong sense of self-worth and expectation that other people are generally accepting and responsive.

Working to change attachment style:

One of the primary ways to work through attachment issues is to fully appreciate where our own patterns come from because sometimes it’s not quite as obvious or transparent as all this suggests. These relationships and patterns in relationship start from our primary attachment ties from the very start of our lives – a time that we don’t have tangible memories of – and our perspectives of these relationships are significantly coloured by the imbalanced nature of that relationship. Very rarely to young children determine that there is something wrong with our parents/caregivers abilities and indeed our (literal) survival depends on believing quite the opposite. Instead, we usually develop a belief that there is something inherently wrong with us, and this is where we must start when we work with attachment wounds.

As I mentioned at the start, there are a range of other resources where you can learn more about your own attachment style:

- The Attachment Project: https://www.attachmentproject.com/blog/four-attachment-styles/

- Simply Psychology: https://www.simplypsychology.org/attachment-styles.html

- Attached (book) by Dr Amir Levine and Rachel Heller

If you’d like to explore your own attachment wounds or better understand your attachment style, and would like a safe space to talk about your mental health, please get in touch with us: www.theabaker.com.au / hello@theabaker.com.au / 03 9077 8194.