Imposter phenomenon

When I sit down to write a blog every Sunday morning, I often draw on things I’ve listened to (podcasts, workshops and the themes of things that have come up in session with clients during the preceding week) and sometimes I write from a very personal place. This week I’m going to vulnerably (it feels like that anyway) share about something that I have been personally working with and has been especially loud in my own head this last week. I’m talking about what it feels like to navigate ‘imposter syndrome’ or ‘imposter phenomenon’ (which I’ll explain a bit later on is the term that I prefer and will encourage us all to use moving forwards). In all parts of my professional life (and for as long as I can remember) I have struggled with imposter phenomenon. When I attend professional development training, I sit in the room surrounded by Clinical Psychologists and Psychiatrists and have the pervasive thought, “any second now they’ll realise I’m an idiot and I shouldn’t be here.” I say as little as possible, try not to answer questions and hope that I can get out without being found out. Whenever I have conversations with people that are objectively more qualified or been working in the field longer than me, I run my responses over and over in my mind with a running commentary that sounds something like, “urgh, what did you say that for? That was SO dumb! They’ll never want to work with you again now!” However, since I’ve started my PhD my imposter part has been having an absolute party! In the middle of October, I have to present my research proposal (and progress to date) in front of the School that I’m part of at Deakin and a panel of academics who will spend an hour or so asking me questions about the 12,000+ words that I’ve written so far. I feel sick every time I think about it and so it’s not surprising that I’ve been spending a lot of time trying to work through this issue.

What is imposter phenomenon?

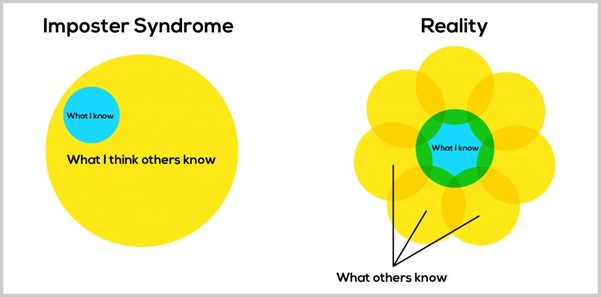

Imposter phenomenon is considered to be a behavioural health phenomenon characterised by self-doubt around intellect, skills, or accomplishments and means that people struggle to attach to their success or achievements (Huecker et al. 2023). People struggling with imposter phenomenon experience pervasive feelings of self-doubt, anxiety, depression and / or fear of being exposed as a fraud in their work despite objective evidence of their successfulness (Bravata et al. 2019). They struggle to accurately associate their performance with their actual competence (Clance and Imes 1978).

Two psychologists (Clance and Imes) first described imposter phenomenon back in 1978 when their focus was on high-achieving professional women, but more recent research has documented these feelings of inadequacy amongst men and women, across a range of settings (academia, corporate, legal, medical/healthcare) and amongst multiple ethnic and racial groups. Notably there has been no research to date focusing on non-binary or gender diverse groups.

Imposter phenomenon is not a mental health condition and does not appear in the DSM 5 or the ICD 11 though both recognise low self-esteem and sense of failure as elements of depression. There is some research that suggests there is a link between imposter phenomenon and job performance, job satisfaction and burnout. For some people these crippling fears can result in procrastination and the ‘failure to launch’ on projects or endeavours, whilst for others that internalised fear only serves to drive their perfectionistic or workaholic traits.

Shifting the perspective:

One of the big challenges when working with imposter phenomenon is that because it’s hard to talk about it becomes a personal rather than an institutional issue. More recently there’s been a shift around looking at why some people (disproportionately women and people of colour) in some of these institutions (academia, corporate, legal, medical/healthcare) are more likely to struggle with feelings of inadequacy and we’re starting to understand that it’s very hard to feel like you’re adequate in a space if you can’t find role models who are like you. If you feel like you don’t belong it makes sense that the focus becomes centred on the need to prove your worth via exceptional achievement.

Tips for working with your imposter part:

- Understand where your imposter part comes from – then make friends with it!

- Assess evidence – make a list of evidence of your competence, keep messages / emails where you’ve had positive feedback or successes and re-read them!

- Refocus on your values

- Practice self-compassion

- Connect to others who look like you in your field – and vulnerably share how you’re feeling (you won’t be the only one!)

- Practice getting back into your body – breathwork, yoga, meditation, physical activity

If this blog has brought up something in your life that you’d like the space to explore, we have a team of trauma-informed therapists at Thea Baker Wellbeing and we have IMMEDIATE availability – please reach out to us at: hello@theabaker.com.au / 03 9077 8194.

Huecker MR, Shreffler J, McKeny PT, et al. Imposter Phenomenon. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Bravata DM, Watts SA, Keefer AL, Madhusudhan DK, Taylor KT, Clark DM, Nelson RS, Cokley KO, Hagg HK. Prevalence, Predictors, and Treatment of Impostor Syndrome: a Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020 Apr;35(4):1252-1275

Clance PR, Imes SA. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1978;15(3):241–7.

Hawley K. Feeling a Fraud? It’s not your fault! We can all work together against Imposter Syndrome [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 April 16].

Harvey JC, Katz C. If I’m So Successful Why Do I Feel Like a Fake? New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1985.